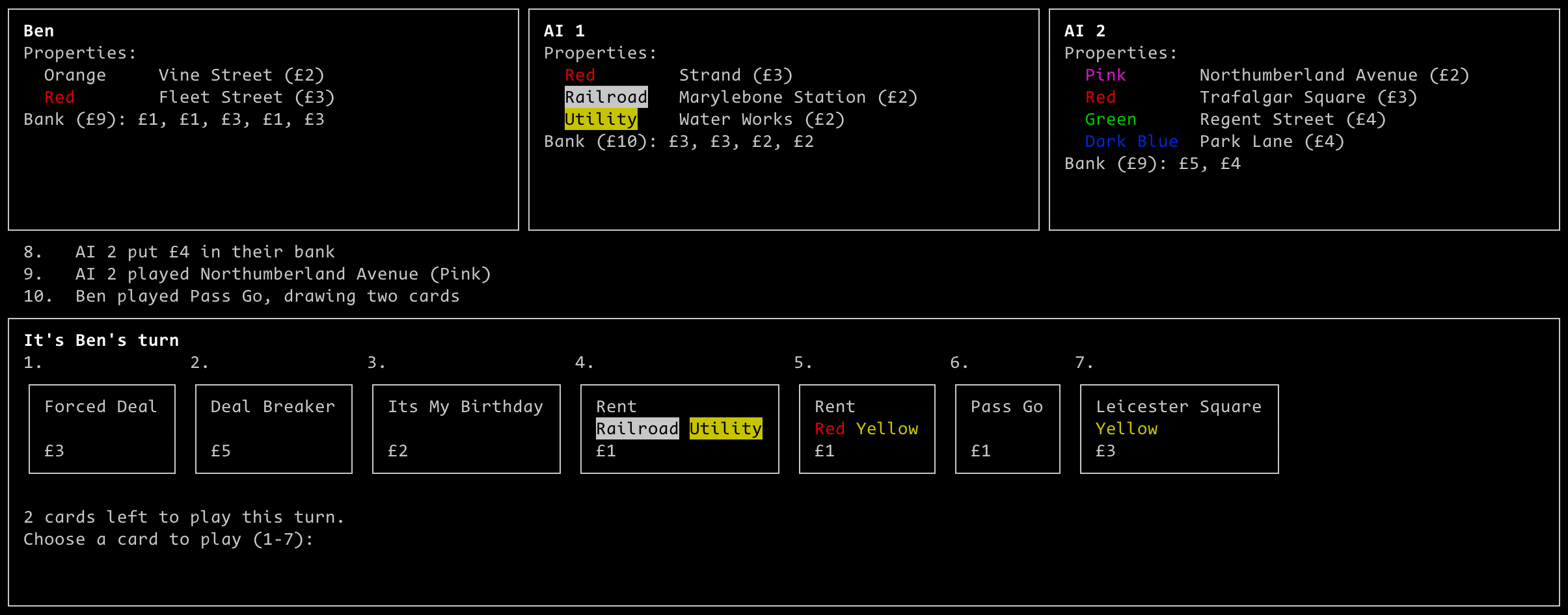

Online Card Game in the Terminal

I recently got hooked on to the Monopoly Deal card game by a close friend in London and, after buying my own set, have been obsessively playing with my research group at lunchtimes for the past month and a bit.

Life recently has been very busy (and very fulfilling), but I took a great deal of time over the past three weeks to implement the game myself and have been loving having a personal programming project again. Now that I’ve finished, I will try to find something else to start to avoid the inevitable post-project slump…

Oh Curses!

Curses is an ancient C library for drawing nice interfaces in the terminal. It provides lots of useful (if arcanely named) functions for drawing boxes, splitting the screen into subwindows, and so on. I found it very pleasant to work with the built-in Python API.

However, I wasn’t able to figure out how to get more than the eight basic terminal colours, so the brown and orange properties remain sadly uncoloured.

Linters

I’m doing lots of theory work now in my day job, so I’m trying to continue improving my software engineering skills with personal projects. Part of this was using Python’s various linters from the start of the project, to catch some of my bad choices early on. I used ruff and pylint to cover style, and mypy to hack onto Python the static typing I so love from OCaml. It’s a little awkward, but much better than the duck-typing insanity I remember from my early years of programming. I added bandit to check security for good measure.

Playing Against the Computer

I wanted to implement a basic AI opponent to play against, and came up with an interesting way of representing an AI’s action as a hierarchy of classes somewhat representing a decision tree. Class instances could also store data, for example a targeted player or property.

...

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class TargetedActionPlan(ActionPlan):

target: player.Player

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class WildRentPlan(TargetedActionPlan):

colour: cards.PropertyColour

rent_amount: int

...

I realised later that this is a bit like the command design pattern from the great Game Programming Patterns book by Bob Nystrom. It would be interesting to use this framework for the real player’s interactions too, rather than their current hardcoded state.

The AI then does a greedy search, generating every possible usage of the cards in its hand, and evaluating how the game state would change accordingly. There is then an evaluation function for the game state that lets us choose the “best” move. Monopoly Deal is such a luck-based game that this creates a surprisingly intelligent opponent, and hand sizes are small enough that this is very fast.

However, if you wanted to implement it, a better AI would consider the impact of playing multiple cards in a row and would factor in a probabilistic model of which cards are in the deck and in the other player’s hands. That’s a little above my pay grade however.

Just Say No!

Just Say No is a card included in the Monopoly Deal game that allows you to nullify someone’s action if it is targeted at you. For example, if you have a wonderful Mayfair property and your conniving weaselly friend tries to steal it with a Sly Deal card, you can crush their dreams by throwing your Just Say No card down. This is a very fun part of the game, but the synchronous nature of how I implemented remote play meant that, by a naive implementation, if you were targeted by an action you would be prompted to let the action occur or use your Just Say No card. The fact the game had frozen would obviously expose the fact that you had this card. There are ways to get around this problem, but I decided to just say no and leave it out.

Client-Server Play

One area that I’ve not implemented very professionally is how the client and server communicate for remotely playing over the network. When the server needs player input to carry on the game, it sends a raw string with the function name over the network and synchronously waits. The client receives this string, compares it in a big table and then runs the requested function, sending back the requested data, again as a raw string. None of these messages are self-identifying; data is sent and parsed in a hardcoded order that is very brittle and hard to test. But, this wasn’t what I was most interested in for the project and so I don’t feel too bad about it. Asynchronous IO and standardised request-response protocols are something I’d like to look into for the future though.

I was looking forward to playing the remote version with my research group colleagues, but the university wifi appears to obfuscate IP addresses in some way, so we couldn’t connect to each other.

Alas, a very fun project nonetheless.