Tic-Tac-Toe in x86 Assembly

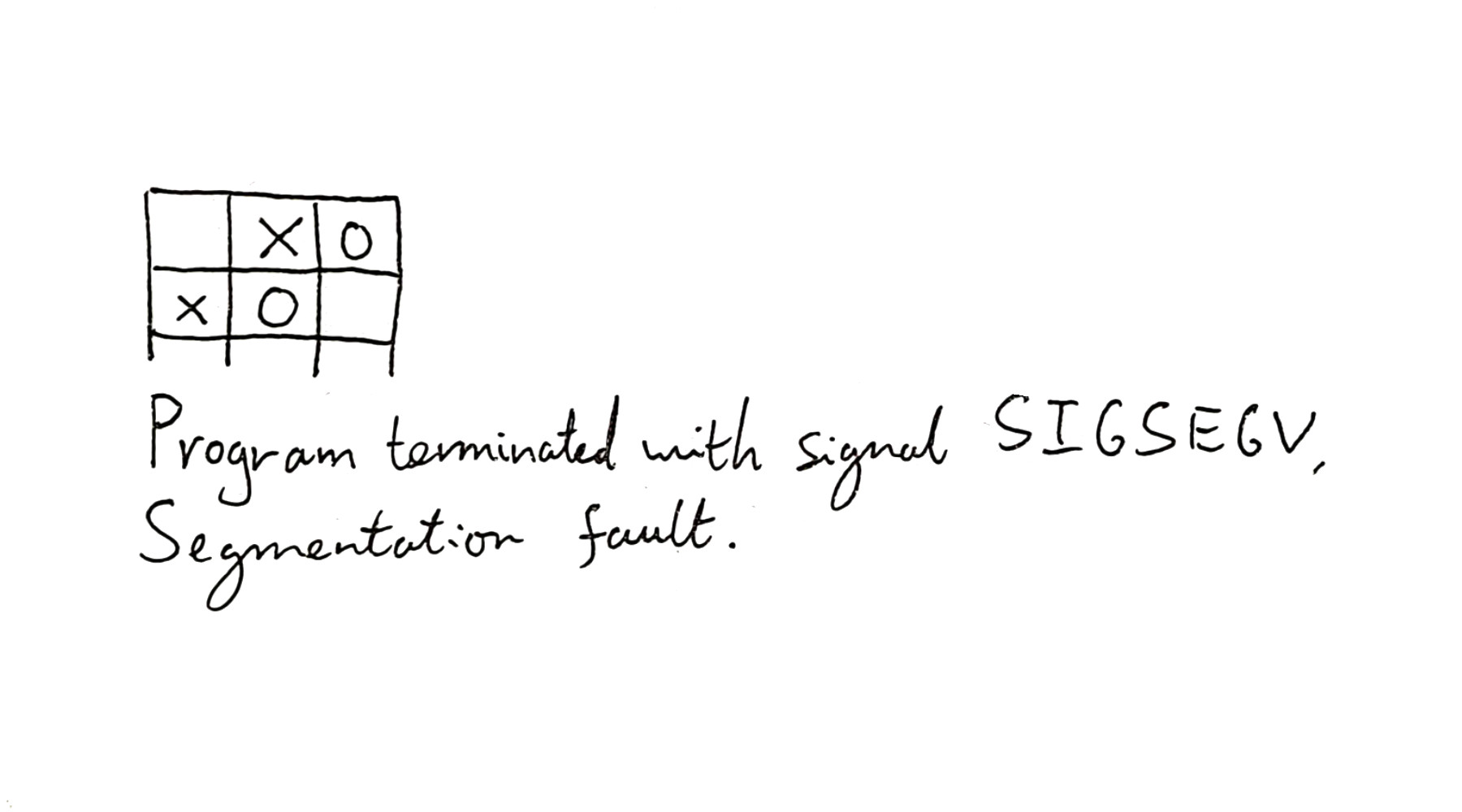

The story of RollerCoaster Tycoon’s development in assembly by Chris Sawyer has an almost mythical status among programmers, and I’ve always felt like assembly programming was a mysterious and arcane art, reserved for wizards, EE engineers, and other magical creatures. To learn it for myself I implemented Tic-Tac-Toe, something I’d find trivial in any real language, but an interesting challenge with no libraries and only Linux syscalls to help me.

You can try my implementation with Docker:

docker run -it benmandrew/ttt86:latest

The Dreaded ABI

You’ve probably heard of an application programming interface (API), which constrains how a client interacts with a high-level service. An application binary interface (ABI) is the same but for the lowest-level, defining for example how data should be passed from a function caller to the callee. The reason we need this in particular is because in assembly we don’t have variables, we have registers which are shared by your whole program. While you may have stored some important data in the rax register for later use, any function you call can choose to overwrite it for its own use, clobbering the register. When the function returns and you then want to use your stored value, you’ll be in for a nasty shock — and a painful debugging experience — when you find something completely different. The ABI is a gentleman’s agreement with yourself of which registers are preserved, and can be trusted to keep their value, and which are volatile, and can be changed by other function calls.

Volatile registers can then be used very locally for temporary values, when we know that there are no function calls between their initialisation and usage. However, the astute reader will wonder how we can possibly use preserved registers if we have to guarantee that their contents are maintained. The solution to this is a sleight of hand where, if a function wants to use a preserved register, it will first push the original contents onto the stack in the prologue of the function, and once it’s done, in the epilogue of the function will pop the value back into the register before returning. From the point of view of the caller, both before the function call and after control is returned, the preserved register kept its value.

Any proper language will do this monkey work for you during compilation or interpretation, but in learning assembly you should keep a language reference open at all times and be very very careful of which registers you use.

As an example, let’s look at a naive implementation of the Fibonacci function using recursion. The parameter is passed in by the rdi register and the output is returned via the rax register. By convention, the first parameter argument is passed through the rdi register and the return value through rax. You can see that the preserved registers I use are pushed onto the stack at the beginning and popped at the end to prevent clobbering. If you want to know more you can check out this reference which I found very useful when learning.

fib:

push r12 ; Push preserved registers onto the stack

push r13

dec rdi ; Decrement input value

mov r12, rdi ; Save decremented input value for second fib call

call fib ; First recursive call

mov r13, rax ; Save returned value to prevent second fib call clobbering it

mov rdi, r12 ; Put saved input value back into first parameter register

dec rdi ; Decrement input value again

call fib ; Second recursive call

add rax, r13 ; Sum the values of the two recursive calls

pop r13 ; Pop values back into registers to preserve them

pop r12

ret ; Return

The Tiniest Binary

Instead of using provided C functions from libc, we can interact with the kernel directly through syscalls. This is done by using a special syscall instruction, and I use it mostly to write to the terminal and read user input. Doing this allows us to store only our code in our output binary. Otherwise, assuming static linking of libc, our binary would be vastly larger. In total my binary comes out to 11.3KB, and a C “hello world” application using printf comes out to 832KB.

Docker

I wanted to package the binary up into a Docker image so that people could run it without installing its dependencies, and I took it as a challenge to try to minimise the size of the image as much as possible. I first used alpine as a base to build the binary and run it with CMD, which came out to 25.6MB. Seeing that alpine is only 8.32MB itself, I realised that not only were all of the files in the working directory being included in the final image, but so too were the dependencies that I needed to build the binary. To fix this, I used a multi-stage build with a second stage that takes only the binary from the first builder stage, dropping the image size to 8.32MB — this is alpine plus the imperceptible binary.

I was happy with this and didn’t think it was possible to reduce further, but I then discovered that Docker runs syscalls on the host kernel, and so I don’t need Linux in the image at all. Using the empty scratch image in the second stage, I dropped the image size to 11.3KB, which is 1.71KB when compressed. Pretty good.

Aside: Arch Linux

The personal dev machine I usually use is an M1 Macbook Pro (kept from my last job, thank you French labour laws), which notably is based on ARM, not x86. After about five seconds of researching how to write ARM assembly for the Darwin architecture, I realised that that would be horrible and that I should do x86 instead. I busted out my old ThinkPad T450 that got me through my third year of undergrad — bought after my last laptop had an unfortunate run-in with my cup of coffee — and realised I’d put Ubuntu server on it at some point and forgotten the password. I thought I’d take the opportunity to install Arch Linux and use it for this project. It’s an old laptop that struggled even with Ubuntu, but Arch is very snappy, and it was both informative and very fun doing all of the configuration. Arch’s minimalism is something I’d like to experiment more with in the future.

Conclusion

Overall, learning assembly was exciting and informative, but I couldn’t imagine implementing any larger of a project in it. Not because it’s superhumanly difficult, but just because of how dreary and dull it is to spend most of my time thinking about calling conventions. Occasionally you hear people argue that you can write something in assembly for extreme performance, but that idea is not only pointless, but actively harmful. Modern C compilers will write better assembly than you any day of the week, and unless you know the exact details of your target processor’s architecture you shouldn’t even attempt it. With out-of-order execution, pipelines hundreds of stages deep, and cache hierarchies supporting multiple in-flight requests, the notion that fewer instructions is automatically faster is pure fantasy.

Mostly, this project has made me grateful for high-level languages and modern tools. Thanks for reading.